Nancy Lindborg tweets about USAID's new mission statement. USAID's new mission statement puts into words a sense of what the agency as a whole is meant to be doing: purusue the goal to end extreme poverty by 2030 Photo by: Devex

The

U.S. Agency for International Development launched a brand new mission statement Wednesday. It’s the latest move by USAID to reconcile limited resources with ambitious goals, and it’s in line with an international donor landscape more focused on achieving results than on funding projects in perpetuity.

Now, when asked what they do for a living, U.S. development professionals stationed in South Sudan, Georgia and Cambodia, or at headquarters in Washington, can all answer:

“We partner to end extreme poverty and promote resilient, democratic societies while advancing our security and prosperity.”

Is USAID’s new mission statement wide open for interpretation? Sure. Is it chock-full of development buzzwords that are exceedingly difficult to define let alone measure? Absolutely.

But with it, the Obama administration is enshrining its new ambitious goal to end extreme poverty (by 2030) into its lead aid agency’s mission. It is also incorporating several themes from the emerging U.N.-led post-2015 global framework such as inclusive growth, resilience and the importance of peace, democracy, and security to development — drawing on lessons from the Arab Spring as well as droughts and other recent disasters in the Horn of Africa, Sahel and Philippines.

Even if the statement seems designed to please everyone, by putting into words a sense of what the agency as a whole is meant to be doing — and by arriving at those words through consultation with over 2,600 agency staff and partners around the world — USAID’s leadership has taken a step towards legitimizing and defining the role of the development professional in executing U.S. foreign policy.

Here’s why words matter in this case.

The new mission statement replaces this: “On behalf of the American people, USAID is helping to accelerate human progress around the world by reducing poverty, advancing democracy, empowering women, building market economies, promoting security, responding to crises, and improving the quality of life through investments in health, agriculture, and education.”

It read like a laundry list of initiatives, and many USAID staff members suffer from

initiative fatigue. They’ve said so in internal surveys and they’ve raised the issue during town halls and panel discussions.

But initiatives are an effective means to secure funding from congressional appropriators, even if they do lock that funding into silos and, perhaps, reduce flexibility. Initiatives — like PEPFAR, Feed the Future and Power Africa — can be championed in ways that a general sense of “doing good” cannot. Initiatives turn abstract goodwill into something concrete and fundable.

Is USAID to implement — or contract — a series of ad-hoc programs, loosely bound by their general contribution towards doing good, yet bogged-down by bureaucratic box-checking and subject to the personal interests of powerful lawmakers and unpredictable turns of geopolitical strategy?

Or, does USAID invigorate and empower its staff to analyze challenges and promote change through innovative partnerships and other means, with a common goal in mind?

The old mission statement was framed around a list of activities that USAID does. The new mission statement is framed around the aspirational end goal that USAID and its partners are working toward.

In the 1990s, USAID came close to disappearing. The agency saw huge budget cuts that stripped away much of its expertise and institutional knowledge. The attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, prompted funding to flood back into foreign affairs — to help “win the hearts and minds” of the Afghan people, among other things.

President Barack Obama’s Development Leadership Initiative sought to double the number of USAID Foreign Service Officers and Administrator Rajiv Shah has expressed his desire to “recentralize” past expertise and decision-making. Some of his efforts to do so, like requiring his personal approval for large funding awards, have turned heads among the agency’s implementing partners.

USAID’s workforce is larger and younger than it has been for a long time, and has been rebuilt under the auspices of Obama’s 2010 presidential policy directive to reposition development as a branch, not a servant, of U.S. foreign policy.

With the Afghan transition supposedly underway and USAID’s role in stabilization and reconstruction efforts poised to wind down over the next few years, it is even more critical for the U.S. government’s development enterprise to assert itself as a “premier” agency dedicated to resourcing civilian power so it can accomplish an articulable mission.

In December, I wrote a ”

New Year’s Resolution for U.S. Aid,” suggesting agency leaders use the occasion of the second Quadrennial Development and Diplomacy Review – which is currently underway — to more clearly articulate the role of the “development professional” in U.S. foreign policy. USAID’s new mission statement is a step in that direction.

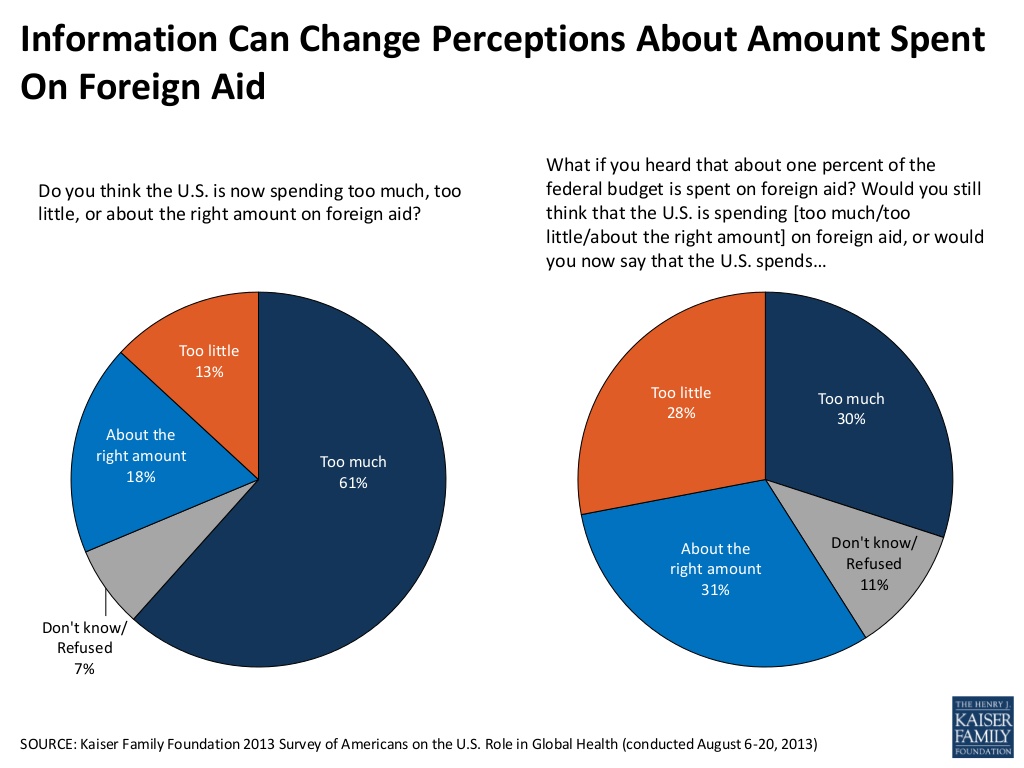

Part of my reason was that foreign assistance is wildly misunderstood by the “average American,” who overestimates U.S. spending levels by 20 times or more and yet, according to some surveys, thinks we should spend more on foreign assistance. (At the same time, when asked how to cut the federal budget and reduce the deficit, foreign aid tends to be among the most popular responses.)

The miscalculation — or total disconnect — seems less to do with innumeracy and more to do with a general lack of clarity about what U.S. foreign aid does. Development professionals lack the sort of professional identity enjoyed by diplomats and military personnel; it is incumbent on the international development community to articulate that identity if it wants a seat at the table where big international decisions are made.

Obviously, a mission statement alone is not enough. So I am encouraged to hear about efforts like the Administrator’s Leadership Council management system, a new open-access, internal database to catalogue all of USAID’s various initiatives in a way that tracks their respective contributions to a common set of extreme poverty-related goals to help determine where funding can be most effective.

The next step for the agency’s leadership is more clearly talking about and showing what it won’t do. For a mission statement to have teeth, it has to serve as a useful benchmark for difficult decisions about where and how to spend money and locate people around the world; and whether or not USAID has the leadership empowered to make those decisions is still a wide open question.

We know that extreme poverty will increasingly exist in fragile and conflict-affected states; and we know these are the most difficult environments in which to administer high-quality and highly-accountable programs.

USAID is getting closer to giving a name and unique mission to the type of professional who forges partnerships that can ease poverty and help build democratic institutions under those challenging conditions. USAID’s mission is still messy. But now the professionals tasked with carrying it out can better explain, and defend, what they’ve signed up for.

Join the Devex community and access more in-depth analysis, breaking news and business advice — and a host of other services — on international development, humanitarian aid and global health.

Bahamas

Bahamas

Barbados remains one of the more popular tourist destinations in the Caribbean, but the numbers have stagnated over the past decade, and a rapid decline in sugar exports has contributed to the toll on the labour force. The value of sugar exports has fallen by two thirds since 2000, with the decline picking up pace in 2008. The jobless rate fell to 7.4 per cent in 2007, but since then the unemployment trend has reversed, and grew for the fifth consecutive year in 2012 to 11.6 per cent. GDP fell by 4 per cent in 2009 and has been relatively static since, with the sluggish economy and growing

Barbados remains one of the more popular tourist destinations in the Caribbean, but the numbers have stagnated over the past decade, and a rapid decline in sugar exports has contributed to the toll on the labour force. The value of sugar exports has fallen by two thirds since 2000, with the decline picking up pace in 2008. The jobless rate fell to 7.4 per cent in 2007, but since then the unemployment trend has reversed, and grew for the fifth consecutive year in 2012 to 11.6 per cent. GDP fell by 4 per cent in 2009 and has been relatively static since, with the sluggish economy and growing Jamaica

Jamaica For decades Jamaica's economy was been driven by exports and tourism industry, but both were hit by the global recession; the economy is still struggling to shake off the effects. Exports of bananas had already been weakening in the early 2000s but plummeted in 2008. Fossil fuels, an increasingly important export for Jamaica, dropped by over half between 2007 and 2009 but have shown steady

For decades Jamaica's economy was been driven by exports and tourism industry, but both were hit by the global recession; the economy is still struggling to shake off the effects. Exports of bananas had already been weakening in the early 2000s but plummeted in 2008. Fossil fuels, an increasingly important export for Jamaica, dropped by over half between 2007 and 2009 but have shown steady Saint Kitts and Nevis

Saint Kitts and Nevis With a population of just 55,000 St Kitts and Nevis is one of the least populous countries in the Caribbean. Over 700,000 visitors arrived on its shores in 2011 - more than 10 for every resident and up threefold from 2000 - but despite buoyant tourism, the wilting sugar and banana industries have weighed heavily on the economy. Exports of bananas and sugar have each declined by over 99% since 2000, as the country lost preferential access to European markets after Latin American producers complained to the World Trade Organisation. GDP per capita had been growing from 2003 to 2008 but has since contracted sharply and at US$12,804 is down 5 per cent in real terms on its 2000 level.

With a population of just 55,000 St Kitts and Nevis is one of the least populous countries in the Caribbean. Over 700,000 visitors arrived on its shores in 2011 - more than 10 for every resident and up threefold from 2000 - but despite buoyant tourism, the wilting sugar and banana industries have weighed heavily on the economy. Exports of bananas and sugar have each declined by over 99% since 2000, as the country lost preferential access to European markets after Latin American producers complained to the World Trade Organisation. GDP per capita had been growing from 2003 to 2008 but has since contracted sharply and at US$12,804 is down 5 per cent in real terms on its 2000 level.

Trinidad and Tobago has the healthiest economy in the Caribbean, thanks largely to its huge energy exports. Oil was long the mainstay, but natural gas is now the dominant export. Tourism numbers, while inconsistent, have remained relatively healthy at around half a million per year since 2000. As a result. GDP per capita is 61 per cent higher than it was in 2000 - the highest increase among all large Caribbean economies for that period. Energy revenues also bolster state finances, with the debt to GDP ratio at a healthy 39 per cent and unemployment has been below 6 per cent since 2007. However, the country was in 2009 clobbered by the collapse of CL Financial, a large conglomerate with tentacles across the Caribbean. Trinidad had to shoulder the bill for its bailout, and four years on is still cleaning up the mess. Crime is still a tremendous problem for Trinidad and Tobago, despite the murder rate creeping down from its peak - 41.1 homicides per 100,000 people in 2008 - since the government was forced to declare a state of emergency in 2011. In 2008 Trinidad and Tobago had the second highest rate in the Caribbean, but the 2011 figure was down a third on this level and is down to fifth place. Nonetheless, the number of homicides has begun to climb again in recent years.

Trinidad and Tobago has the healthiest economy in the Caribbean, thanks largely to its huge energy exports. Oil was long the mainstay, but natural gas is now the dominant export. Tourism numbers, while inconsistent, have remained relatively healthy at around half a million per year since 2000. As a result. GDP per capita is 61 per cent higher than it was in 2000 - the highest increase among all large Caribbean economies for that period. Energy revenues also bolster state finances, with the debt to GDP ratio at a healthy 39 per cent and unemployment has been below 6 per cent since 2007. However, the country was in 2009 clobbered by the collapse of CL Financial, a large conglomerate with tentacles across the Caribbean. Trinidad had to shoulder the bill for its bailout, and four years on is still cleaning up the mess. Crime is still a tremendous problem for Trinidad and Tobago, despite the murder rate creeping down from its peak - 41.1 homicides per 100,000 people in 2008 - since the government was forced to declare a state of emergency in 2011. In 2008 Trinidad and Tobago had the second highest rate in the Caribbean, but the 2011 figure was down a third on this level and is down to fifth place. Nonetheless, the number of homicides has begun to climb again in recent years.

Antigua and Barbuda

Antigua and Barbuda Aruba

Aruba British Virgin Islands

British Virgin Islands Cayman Islands

Cayman Islands Cuba

Cuba Curaçao

Curaçao Dominica

Dominica Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Grenada

Grenada Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe Haiti

Haiti Martinique

Martinique Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico Saint Lucia

Saint Lucia Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Sint Maarten

Sint Maarten United States Virgin Islands

United States Virgin Islands